CFD simulations involving 3D complex geometry have become the norm, however, this hasn’t lessened the…

The evolution of CFD at Garry Rogers Motorsport

Look at the evolution of fluid dynamics and you’ll quickly realize that our understanding of the subject has advanced a great deal in a relatively short space of time. To read the story of American entrepreneur George Westinghouse, his ideas and inventions reference the avant-garde physicists of the period like Lord Kelvin and Sir George Stokes. Anyone in the CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) world will instantly recognize those names, as they’ve made great contributions to our understanding of the way fluids interact and underpin a lot of what we enjoy doing. It’s hard to imagine a time when we didn’t have a unit of Kelvin, or the Navier-Stokes equations.

One point to make from this is that everything has to start somewhere. There is a persistent belief that CFD is a very demanding beast, that will require a level of knowledge people don’t have and that the resources to run it are impossibly expensive or difficult to acquire. These thoughts can doom a CFD program before it begins. At Garry Rogers Motorsport, we want to dispel that myth.

With the help of Pointwise and Applied CCM we have been running full car CFD simulations of every GRM Supercar since 2012. It does require a lot of effort, but with the right support, it is indeed very possible, and the knowledge gained is so valuable and it is ours to access whenever we need it. We wanted to recap the experience we’ve had over the years.

THE BEGINNING

First we’ll talk about homologation. For a new vehicle to enter our Supercars championship, it first must be designed around a series of technical regulations. Covering everything from engine, chassis and bodywork design. The downforce and drag generated by the car must be near identical to the other vehicles in the championship. Once the design criteria is met, the vehicle is signed off for eligibility to compete and the bodywork is 3D scanned for scrunitering purposes. Aerodynamic testing in wind tunnels on either the full size car or scale model is strictly prohibited. This is where CFD comes in.

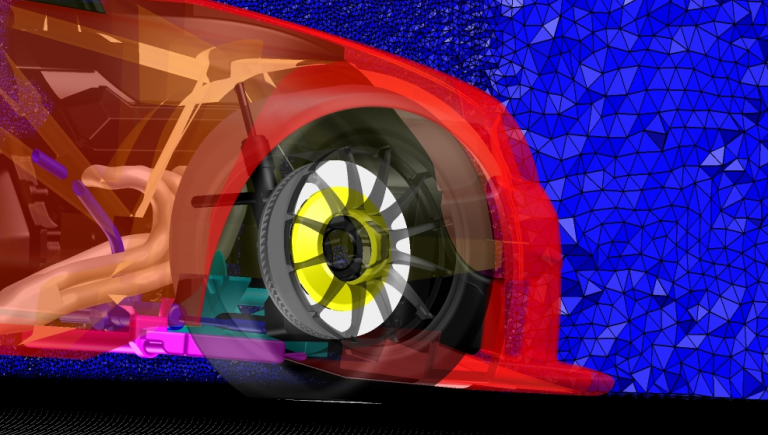

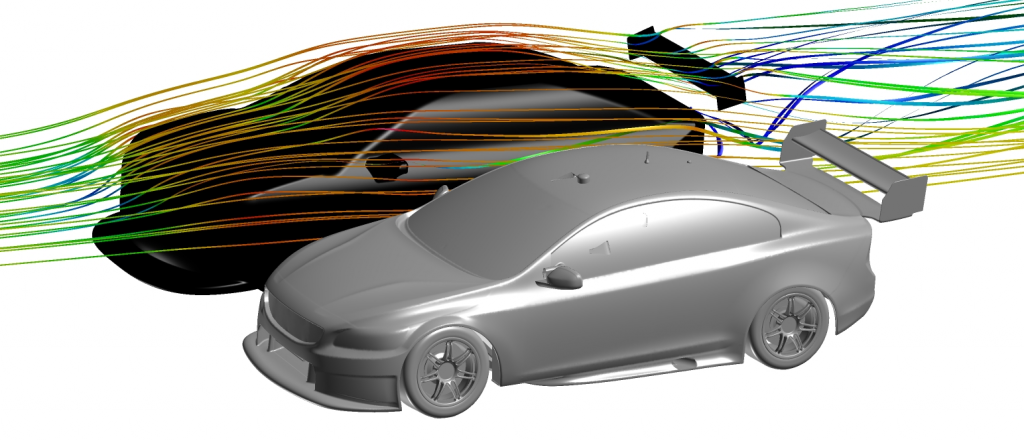

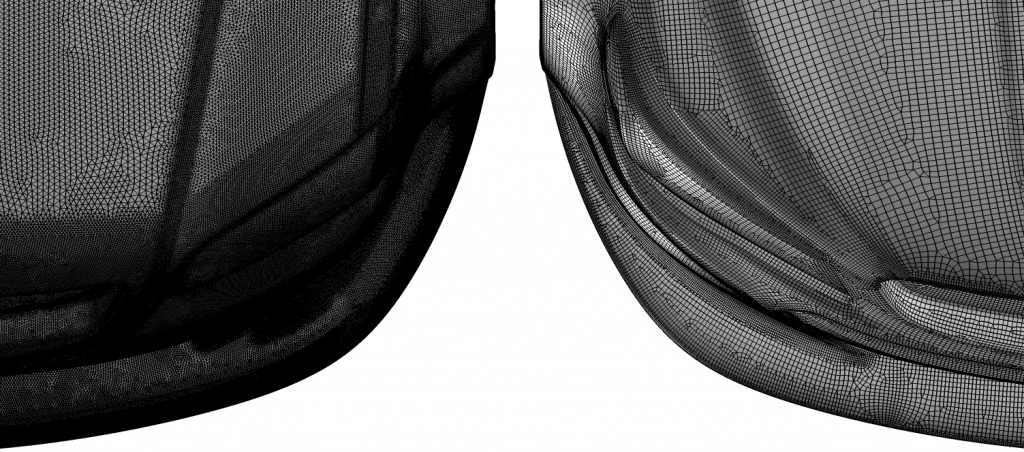

GRM’s first foray into CFD, was with the, battle, hardened VE Commodore which had been in service since 2007. While its attitude was already well understood by our engineers, the CFD promised to deliver very detailed aerodynamic data. We could not obtain this from just cutting laps and reading the cars logged data. Our first CFD model had a mesh you could consider a work of art. Every detail modelled, incredibly smooth convergence. However, this came at the expense of long solver times and up to six hours generating the volume mesh.

This is where Pointwise and Applied CCM stepped in. With Pointwise designed with CFD in mind, it was able to handle the heavy task and cut volume generation times by two thirds. The T-Rex feature captured the boundary layers in exquisite detail. The initial use of Pointwise consisted of importing our already completed surface mesh and inflating the volume so that it linked in with the existing workflow. This saved us weeks of effort not recreating the surface mesh.

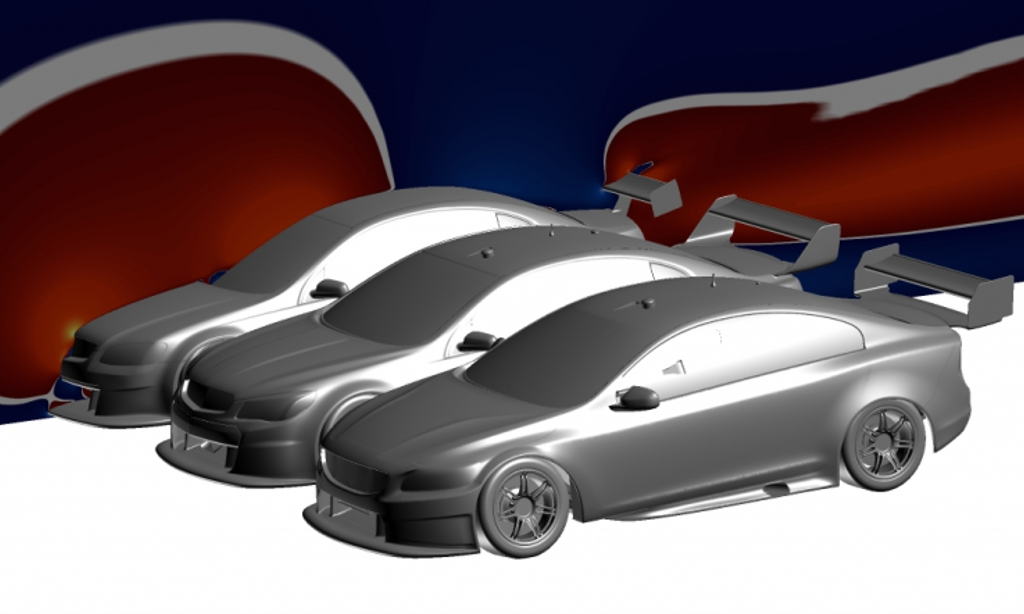

THE CAR OF THE FUTURE

After our first year using CFD, 2013 brought about a big change in the world of Supercars. The updated next generation chassis designated ‘Car of The Future’ (COTF) was introduced and moreover, Holden, the division of GM in Australia, announced that all teams running their marque would upgrade to the new VF Commodore (Chevy SS) to coincide with release of their NASCAR variant in the USA

Early in the year, just as the simulations of the new car were running, a new manufacturer approached us with the brief to design a new Supercar, the Volvo S60. In our previous aerodynamic studies, the design of the car was already locked down. We could only use CFD as a tool for understanding an existing shape, it was essentially for fine tuning the car. The first opportunity by our team to utilize the full car design tool was on the Volvo.

Since the silhouette of the final car should closely resemble the road car, the team developed a design study model that was made up of simple extruded cuts in 3-directions.This represented the vehicle shape to get an idea of flow over the body. An important first step is determining the wing position. It was positioned above the trunk lid, and its angle or position could be easily altered to help us gain an understanding of the wing interaction with the cars body. This model was up and running in two days.

With an idea of the wing placement came the development of the model for manufacture. This design process ran side by side with the CFD. As a new feature was created, it was immediately inserted into the model. The model was run in the software to see any effects of load changes and flow characteristics changes around the car. This gave us many options to take to our homologation aero test, with a good idea of the effect they would have on the overall balance of the car. The result of which was the most competitive car in the COTF era.

BACK TO THE COMMODORE

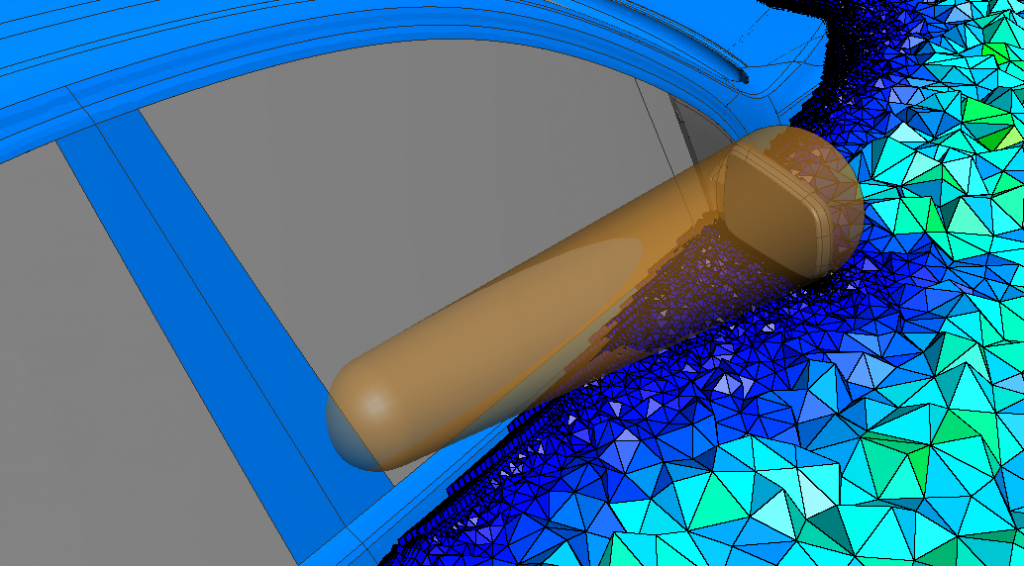

The year 2017 saw a return to the VF Commodore that we had run previously. This event coincided with the recent release of Pointwise V18 and the introduction of unstructured quad and hex meshes into the program. The quadrilateral dominant meshing algorithm had the potential to greatly reduce the cell count on our meshes without losing the accuracy. We had a mesh of the Volvo on hand at the release and within an hour had cut the surface mesh count by 20%. Generating the volume mesh was just as impressive, from our first models five years earlier with element counts exceeding 190M, we now produce full car models with an element count of ~74M.

While Pointwise has always been working hard to find efficient ways to reduce the element count of our models, we find other ways to put them back in. A fantastic feature introduced in V18 were sources, these gave us greater control over the local volume mesh in areas of interest. While the running of a stable RANS code means that we expect a degree of error in the prediction of forces present in a vehicle with large separations, we want to make the error as small possible. We use these sources to target areas like the mirrors, wing and underbody diffuser tunnels.

While incorporating these new features into our meshes for improvement we took the opportunity to change our solver as well. With our long history with Applied CCM, Caelus was our natural choice, developed and supported by Applied CCM (forked from OpenFOAM® and has proven to be very stable, running our full car simulations. Caelus will remain our solver of choice into the future.

PRESENT DAY

The ZB Commodore arrived in 2018, while we did not have any input on its development, that won’t stop us from utilizing CFD to gain an understanding of this cars unique aerodynamics. Many manufacturers today, are trending towards body types for improved fuel economy with smooth raked back rear ends and short trunk lids are the common feature. However, these features make them very slippery, yet tend to generate more lift. To counteract this, the ‘down force’ generating features, must be made more aggressive.

GRM has come a long way since our first full car CFD simulation in 2012. There have been many challenges in getting the most out of our software and computational resources but it has been well worth the effort. In the time that we have been using Pointwise, we’ve seen significant changes to the way we mesh in order to best target projects for their, accuracy, stability and most of all, accurate representation of the real cars. Aligning ourselves with Pointwise and Applied CCM has been one of the keys to our successful CFD program. We always count on them to find better way to help us simulate our cars.

By Scott Burch, CFD Engineer, Garry Rogers Motorsport 2018

3.

The evolution of CFD at Garry Rogers Motorsport